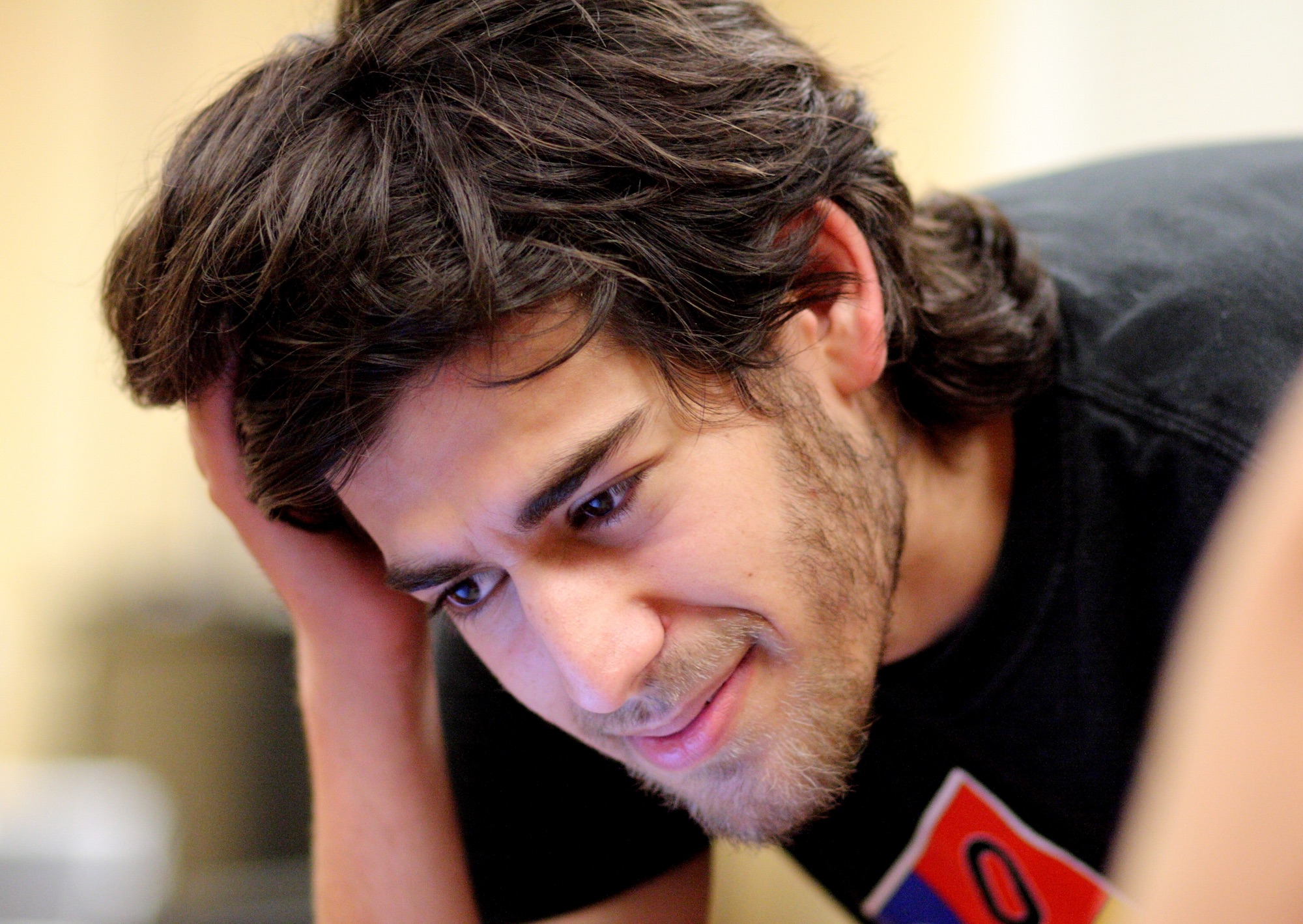

I didn’t know Aaron personally, so there’s no insight I can provide into the person who I’ve read people describe as “a brilliant soul”.

The world is now a worse place

The tech world is abuzz with the news that, at only 26 years old, Aaron Swartz decided to take his own life. I heard about it last night when I opened up Tweetbot, and saw two tweets back-to-back in my timeline:

@al3x :

We lost @aaronsw. — Alex Payne (@al3x) January 12, 2013.

@dcurtis :

Fuck. tech.mit.edu/V132/N61/swart…The world is now a worse place. — dustin curtis (@dcurtis) January 12, 2013.

RSS

Being part of the web world, I certainly knew Aaron by reputation. I first heard about him back when I started tinkering with RSS in 2003. While I may have started a project that simplified RSS for a legion of PHP developers, Aaron literally wrote the spec — and at 14 years old, I might add.

Cory Doctorow had this to say:

I met Aaron when he was 14 or 15. He was working on XML stuff (he co-wrote the RSS specification when he was 14) and came to San Francisco often, and would stay with Lisa Rein , a friend of mine who was also an XML person and who took care of him and assured his parents he had adult supervision. In so many ways, he was an adult, even then, with a kind of intense, fast intellect that really made me feel like he was part and parcel of the Internet society, like he belonged in the place where your thoughts are what matter, and not who you are or how old you are.

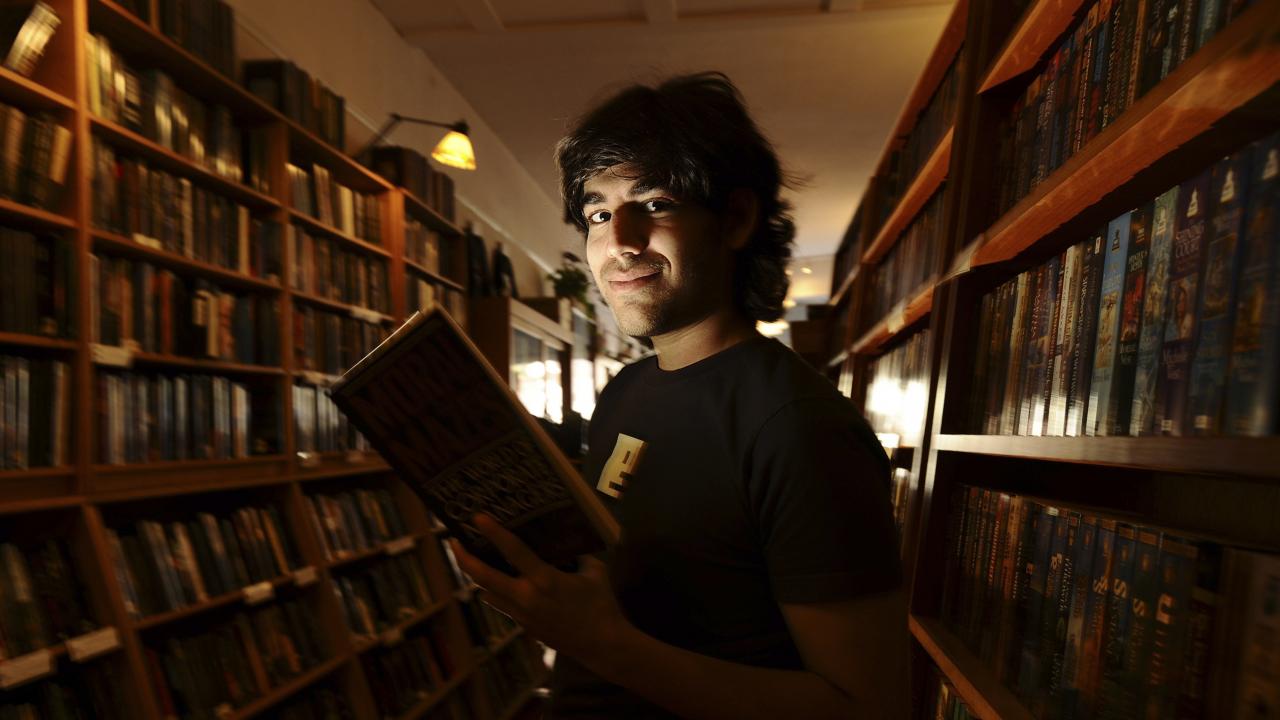

Creative Commons. PACER. Demand Progress.

Every so often throughout the last decade, his name would pop-up around topics that I was also interested in. Creative Commons. Opening up public access to court records. Demand Progress. He used technology to fight for the same sorts of causes that I fight for, evangelize for, or are otherwise close to my heart. Namely:

-

the over-criminalization of American citizens by its government, and…

-

the fact that the people we elect to represent us in government would throw us under the bus in a heartbeat if it meant more money, power and political cachet.

Cory Doctorow continues:

At one point, he singlehandedly liberated 20 percent of US law. PACER, the system that gives Americans access to their own (public domain) case-law, charged a fee for each such access. After activists built RECAP (which allowed its users to put any caselaw they paid for into a free/public repository), Aaron spent a small fortune fetching a titanic amount of data and putting it into the public domain. The feds hated this. They smeared him, the FBI investigated him, and for a while, it looked like he’d be on the pointy end of some bad legal stuff, but he escaped it all, and emerged triumphant.

Aaron was involved in the creation of an organization called Demand Progress, who “works to win progressive policy changes for ordinary people through organizing, and grassroots lobbying. In particular, we tend to focus on issues of civil liberties, civil rights, and government reform.”

It was here where I first learned about the Senate’s proposed PROTECT-IP Act (later renamed “PIPA”), and it’s House sibling, the ill-fated SOPA Act, whose negative repercussions would have been felt for generations to come.

Download too much, go to jail

From a New York Times article dated July 19, 2011:

Demand Progress said on its site that it appeared Mr. Swartz was “being charged with allegedly downloading too many scholarly journal articles from the Web.” It quoted the group’s executive director, David Segal, as saying, “It’s like trying to put someone in jail for allegedly checking too many books out of the library.”

Cory Doctorow:

Aaron snuck into MIT and planted a laptop in a utility closet, used it to download a lot of journal articles (many in the public domain), and then snuck in and retrieved it. This sort of thing is pretty par for the course around MIT, and though Aaron wasn’t an MIT student, he was a fixture in the Cambridge hacker scene, and associated with Harvard, and generally part of that gang, and Aaron hadn’t done anything with the articles (yet), so it seemed likely that it would just fizzle out. Instead, they threw the book at him. Even though MIT and JSTOR (the journal publisher) backed down, the prosecution kept on. I heard lots of theories: the feds who’d tried unsuccessfully to nail him for the PACER/RECAP stunt had a serious hate-on for him; the feds were chasing down all the Cambridge hackers who had any connection to Bradley Manning in the hopes of turning one of them, and other, less credible theories. A couple of lawyers close to the case told me that they thought Aaron would go to jail.

And Larry Lessig:

But all this shows is that if the government proved its case, some punishment was appropriate. So what was that appropriate punishment? Was Aaron a terrorist? Or a cracker trying to profit from stolen goods? Or was this something completely different? Early on, and to its great credit, JSTOR figured “appropriate” out: They declined to pursue their own action against Aaron, and they asked the government to drop its. MIT, to its great shame, was not as clear, and so the prosecutor had the excuse he needed to continue his war against the “criminal” who we who loved him knew as Aaron.

And an article from September by Tim Cushing from TechDirt:

Swartz, the executive director of Demand Progress, was charged with violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, a catch-all designation for “computer activity the US government doesn’t like.” Swartz had accessed MIT’s computer network to download a large number of files from JSTOR, a non-profit that hosts academic journal articles. US prosecutors claimed he “stole” several thousand files, but considering MIT offered this access for free on campus (and the files being digital), it’s pretty tough to square his massive downloading with any idea of “theft.”

Prosecutor as bully

Larry Lessig continues (reformatted paragraphs, mine):

Here is where we need a better sense of justice, and shame. For the outrageousness in this story is not just Aaron. It is also the absurdity of the prosecutor’s behavior.

From the beginning, the government worked as hard as it could to characterize what Aaron did in the most extreme and absurd way. The “property” Aaron had “stolen,” we were told, was worth “millions of dollars” — with the hint, and then the suggestion, that his aim must have been to profit from his crime. But anyone who says that there is money to be made in a stash of ACADEMIC ARTICLES is either an idiot or a liar. It was clear what this was not, yet our government continued to push as if it had caught the 9/11 terrorists red-handed.

Aaron had literally done nothing in his life “to make money.” He was fortunate Reddit turned out as it did, but from his work building the RSS standard, to his work architecting Creative Commons, to his work liberating public records, to his work building a free public library, to his work supporting Change Congress/FixCongressFirst/Rootstrikers, and then Demand Progress, Aaron was always and only working for (at least his conception of) the public good. He was brilliant, and funny. A kid genius. A soul, a conscience, the source of a question I have asked myself a million times: What would Aaron think?

That person is gone today, driven to the edge by what a decent society would only call bullying. I get wrong. But I also get proportionality. And if you don’t get both, you don’t deserve to have the power of the United States government [against] you. For remember, we live in a world where the architects of the financial crisis regularly dine at the White House — and where even those brought to “justice” never even have to admit any wrongdoing, let alone be labeled “felons.”

And again from TechDirt:

There are now 13 felony counts in the new indictment, derived from claims of multiple instances of breaking those four laws. In specific:

- Wire Fraud - 2 counts

- Computer Fraud - 5 counts

- Unlawfully Obtaining Information from a Protected Computer - 5 counts

- Recklessly Damaging a Protected Computer - 1 count

It’s beyond my pay grade to figure out how many years in prison that all could be, when taking into account the complexities of sentencing law. Let’s leave it at a large scary number. Enough to ruin someone’s life.

And the kicker…

So, how do the new charges stack up in terms of a sentence? Tough to say. Each of the charges carries the possibility of a fine and imprisonment of up to 10–20 years per felony. Depending on how many of the counts Swartz is found guilty of, the sentence could conceivably total 50+ years and fine in the area of $4 million. All this over publicly accessed research documents that JSTOR doesn’t even feel the need to pursue further than it did.

In the end

Alan Ellis , a nationally-recognized federal criminal defense lawyer explains:

Nearly 97 percent of all federal criminal defendants will plead guilty. Of the remaining 3 percent who go to trial, as many as 75 percent will be convicted. Thus, nearly 99 percent of all federal criminal defendants will be sentenced. Of that number, 80 percent of defendants will receive jail or prison time.

Specifically:

- 96.9% of federal criminal cases result in a guilty plea. (U.S. Sentencing Commission)

- 75.6% of federal criminal defendants are convicted following trial. (U.S. Department of Justice)

- 99% of federal defendants are sentenced.

- 82.8% of federal criminal defendants receive a prison term. (U.S. Sentencing Commission)

In the end, while nobody knows why Aaron decided to take his own life, I could certainly posit a guess. When the federal government comes after you, you’re pretty much done for. In Aaron’s case, he pissed off the wrong federal prosecutors, and they moved to eviscerate him, legally, over downloading academic journals that MIT provided access to for free.

What a terrible, terrible shame.

Update (2013–01–12)

As the day has gone on, more people have been sharing their thoughts on Aaron, his case, and the person he was.

A post by Aaron Swartz, dated July 2008.

There is no justice in following unjust laws. It’s time to come into the light and, in the grand tradition of civil disobedience, declare our opposition to this private theft of public culture.

We need to take information, wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world. We need to take stuff that’s out of copyright and add it to the archive. We need to buy secret databases and put them on the Web. We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks. We need to fight for Guerilla Open Access.

With enough of us, around the world, we’ll not just send a strong message opposing the privatization of knowledge — we’ll make it a thing of the past. Will you join us?

The official statement from Aaron Swartz’ family:

Aaron’s commitment to social justice was profound, and defined his life. He was instrumental to the defeat of an Internet censorship bill; he fought for a more democratic, open, and accountable political system; and he helped to create, build, and preserve a dizzying range of scholarly projects that extended the scope and accessibility of human knowledge. He used his prodigious skills as a programmer and technologist not to enrich himself but to make the Internet and the world a fairer, better place. His deeply humane writing touched minds and hearts across generations and continents. He earned the friendship of thousands and the respect and support of millions more.

From the post “My Aaron Swartz, whom I loved.,” by Quinn Norton:

He loved my daughter so much it filled the room like a mist. He was transported playing with her, and she bored right into his heart. In his darkest moments, which I couldn’t reach him, Ada could still touch him, even if only for a moment. And when he was in the light, my god. I couldn’t keep up with either of them. I would hang back and watch them spring and play and laugh, and be so grateful for them both.

Expert witness Alex Stamos, in “The Truth about Aaron Swartz’s ‘Crime’":

In short, Aaron Swartz was not the super hacker breathlessly described in the Government’s indictment and forensic reports, and his actions did not pose a real danger to JSTOR, MIT or the public. He was an intelligent young man who found a loophole that would allow him to download a lot of documents quickly. This loophole was created intentionally by MIT and JSTOR, and was codified contractually in the piles of paperwork turned over during discovery.

If I had taken the stand as planned and had been asked by the prosecutor whether Aaron’s actions were “wrong”, I would probably have replied that what Aaron did would better be described as “inconsiderate”. In the same way it is inconsiderate to write a check at the supermarket while a dozen people queue up behind you or to check out every book at the library needed for a History 101 paper. It is inconsiderate to download lots of files on shared wifi or to spider Wikipedia too quickly, but none of these actions should lead to a young person being hounded for years and haunted by the possibility of a 35 year sentence.

Update (2013–01–20)

I’ve continued to add to the links below as I’ve come across them, but a few more interesting things are beginning to shake-out from Aaron’s prosecution.

Scott Horton from Harper’s Magazine writes (Emphasis mine):

U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz is fighting to hold on to her job, and to avoid an embarrassing grilling in Congress and possible professional disciplinary proceedings. Her prospects look grim. Rep. Darrell Issa (R., Calif.), chair of the House Committee on Oversight is pledging a vigorous and critical inquiry into her management of the dubious criminal prosecution of Aaron Swartz, one of the greatest computer prodigies of his generation, who committed suicide a week ago, apparently convinced that out-of-control prosecutors had destroyed his life. […]

At funeral services in Highland Park, Illinois, on Tuesday, Swartz’s father charged that his son had been “killed by the government.” While some might ascribe this to the anguish of a bereaved father, scholars and investigators poring over the record of the Swartz prosecution are increasingly shocked at the scope and outrageousness of the prosecutorial misconduct that he faced. […]

Although each of these counts bordered on the preposterous, Ortiz and Heymann clearly reckoned that at least one or two would stick during the jury-room bargaining process. More to the point, they assumed that the risk of their success even on bogus charges would be enough to pressure Swartz into accepting a guilty plea on all the counts in exchange for a reduced sentence — which is what they offered him. The process was fundamentally corrupt and shameful. But observers of the American criminal-justice system also know that it was a common one.

I first learned about this corrupt little trick, long-since leveraged by federal prosecutors, when my best-friend-since-childhood made a stupid mistake one evening that was technically a felony offense — he viewed a 30-second video clip of somebody else committing a felony.

This is the same thing that police do when they’re investigating a bank robbery. The same thing that news anchors do when they show a security tape of people smashing through the front-doors of an Apple Store to steal iPads, “more at eleven”. Had he walked by and seen it happening through a window, he wouldn’t have been prosecuted. But he saw a half-minute recording and they threw the book at him. It’s very much like how prostitution is illegal, but if you record the act, suddenly it becomes porn. Perfectly legal.

50 hours of community service would have been plenty to correct the mistake he made and make him pay more attention to his actions in the future. Instead, trumped-up charges by federal prosecutors resulted in him being sentenced to 2 years in a federal penitentiary, followed by 5 years under probation, and another 15–20 years on the Sex Offender Registry living as a social pariah.

(Studies by the U.S. Justice Department and other organizations show that recidivism rates are significantly lower for convicted sex offenders than for burglars, robbers, thieves, drug offenders and other convicts.)

He lost his home, his career, many of his friends, and because of his registry status he can’t find work — all because he made a stupid mistake. He’s doing everything he possibly can to re-assimilate back into society, but society doesn’t want him. His life was ruined. Fortunately, he’s smart, well-spoken and a hard worker. He was able to start two companies and is able to provide for his wife and 3 children. One of those companies is dedicated to helping people who were likewise abused by the federal justice system and have experienced the injustice of the Bureau of Prisons.

But I digress…

Timothy B. Lee, from Ars Technica, follows-up on Aaron’s Law:

On Tuesday, Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) took to the pages of reddit to introduce legislation she dubbed “Aaron’s Law.” Lofgren’s bill would modify the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the basis for Swartz’s prosecution, to clarify that its definition of unauthorized access “does not include access in violation of an agreement or contractual obligation, such as an acceptable use policy or terms of service agreement, with an Internet service provider, Internet website, or employer.” It would make a similar change to the wire fraud statute.

The language was praised by Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig, a friend of Swartz whose wife organized his legal defense fund. “This is a CRITICALLY important change that would do incredible good,” Lessig wrote on reddit. “The CFAA was the hook for the government’s bullying of @aaronsw. This law would remove that hook.”

More links…

- A Chat with Aaron Swartz (Blogoscoped)

- Raw Thought: The Weblog of Aaron Swartz in Markdown, PDF, and ePub (GitHub)

- Carmen Ortiz Strikes Out (Harper’s)

- Still More About The Death Of Aaron Swartz (Esquire)

- How the Legal System Failed Aaron Swartz (The New Yorker)

- Darrell Issa Probing Prosecution Of Aaron Swartz, Internet Pioneer Who Killed Himself (Huffington Post)

- Lawmakers slam DOJ prosecution of Swartz as ‘ridiculous, absurd’ (The Hill)

- Did Prosecutors Go Too Far In Swartz Case? (NPR)

- 25,000 People Sign Petition to Remove Aaron Swartz’s Prosecutors (Mashable)

- “Aaron’s law,” Congressional investigation in wake of Swartz suicide (Ars Technica)

- Farewell to Aaron Swartz, an extraordinary hacker and activist (Electronic Frontier Foundation)

- Feds go overboard in prosecuting information activist (Ars Technica)

- Be free (resource.org)

- Aaron Swartz, Precocious Programmer and Internet Activist, Dies at 26 (New York Times)

- AaronSW may have left everything to Givewell, an efficient meta-charity (Hacker News)

- Aaron Swartz’s legacy (Michael Roberts)

- Aaron is dead. (Sir Tim Berners-Lee, W3C)

- Aaron Swartz (Mark Bernstein)

- Aaron Swartz (Brent Simmons)

- Soulmate lost. RIP Aaron Swartz. (Alex Dong)

- Aaron Swartz and me, over a loosely intertwined decade (Ars Technica)

- Aaron Swartz (JSTOR)

- Aaron Swartz, hero of the open world, dies (archive.org)

- Remembering Aaron Swartz (ThoughtWorks)

- US Attorney Chided Swartz On Day of Suicide (Slashdot)

- Remember Aaron Swartz (1986 – 2013) (TorrentFreak)

- Our tribute to Aaron Swartz (Science Citizen)

- $10,000: The Aaron Swartz Memorial Grants (Aaron Greenspan)

- Statement on behalf of MIT (L. Rafael Reif)

- Why Am I So Upset About Aaron Swartz’s Suicide? (John Atkinson)

- The Criminal Charges Against Aaron Swartz (Part 1: The Law) (The Volokh Conspiracy)

- A Data Crusader, a Defendant and Now, a Cause (New York Times)

- Anonymous hacks 2 MIT websites in the memory of web activist Aaron Swartz (hacker9)

- Remembering Aaron Swartz: Commons man (The Economist)

- Remembering Aaron Swartz (danbri.org)

- MIT and Aaron Swartz (Crooked Timber)

- Prosecutor pursuing Aaron Swartz linked to suicide of another hacker (RT.com)

- Towards Learning from Losing Aaron Swartz: Part 2 (Stanford Law School)

- Aaron Swartz: Idealist, Innovator—And Now Victim (The Daily Muse)

- “We’ve lost a fighter”: Hundreds gather to mourn Aaron Swartz (Ars Technica)

- Aaron Swartz’s Lawyer: MIT Refused Plea Deal Without Jail Time (Gothamist)

- The Suicide of a Federal Criminal Defendant (PCR Consultants)

- Aaron (Waxy.org)

- I conceal my identity the same way Aaron was indicted for (Errata Security)

- Aaron Swartz & A Culture of Denial: Depression & Suicide in Tech (PsychCentral)

- The Tragic Case of Aaron Swartz: Unequal Justice for Web Activists vs Health Care Corporate Executives (Health Care Renewal)

- MIT Closet Allegedly Used by Aaron Swartz (Cryptome)

- Edward Tufte’s defense of Aaron Swartz and the “marvelously different” (Dan Nguyen)